Mining – the benefits are with us in daily life, but so are the impacts.

Impacts to our lands, our waters and our bodies.

Mineral extraction moves on a continuum of impact, from initial exploration through to invasive exploitation.

In the earliest phases – prospecting and exploration – impacts may be less severe, but they are also less regulated, and generally lack any requirement for rehabilitation of the site. And while impacts may be less severe, the site disturbance can be extreme, with complete removal of the vegetation and so total loss of ecological function. Prospecting and exploration on the ground usually involve motorized access, as well as activities such as exploratory stripping, or removal of the ground cover; excavation; and diamond drilling, which also produces disruptive noise, as well as acidic waste water. More advanced exploration can include sinking of mine shafts and actual ore production. All of the related human impacts of road access, fuel spillage, and waste production accompany these activities.

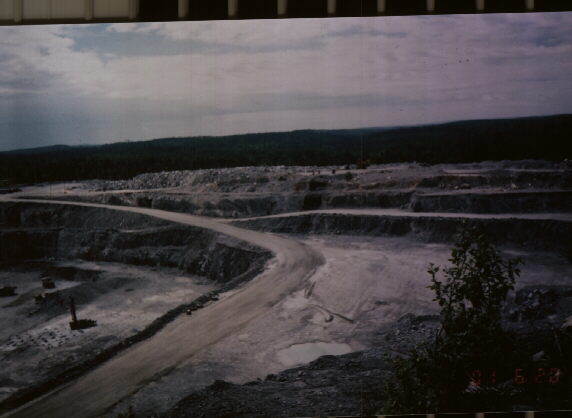

The mining process requires massive removal of soil and rock to retrieve the valued ore. The result is huge amounts of waste rock, which often contain toxic heavy metals and acid-generating materials. The ore goes through a number of processes on its way from mine to market, the first of which is a primary separation of the desired mineral from the other constituents of the rock – a process which produces large quantities of contaminated water and huge amounts of tailings, which are the “left-overs” of the separation process.

The greatest problems created by the mining process are as a result of the waste rock and tailings being exposed to oxygen and precipitation, which generate acidified water, which contaminating surface and ground water and area streams, rivers and lakes. Responsible mining operations would require the waste rock to be reclaimed or capped with an impermeable material, such as clay, but in most cases in the Great Lakes Basin – particularly in the thousands of abandoned and orphaned sites – the waste rock and tailings are left exposed, creating huge problems with acid mine drainage, heavy metals contamination, erosion and sedimentation and chemical process pollution. The last stage “mining sequence” is one of the most critical, in terms of environmental damages. Metals occurring in compounds such as sulphide or oxide minerals, like copper or nickel, are isolated in their metallic state by smelting, where the sulphur is turned into the gas sulphur dioxide, which mixes with precipitation to become acid rain. In recent years, the emission levels of metal smelters have been substantially reduced, but cost and profit still draw the line on the toxic side of zero discharge

UnderMINING Superior, 2001